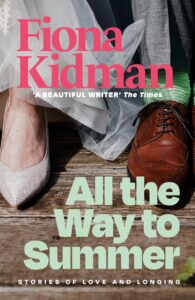

[Gallic Books; 2024]

I like Fiona Kidman’s stroppy women. Stroppy, a bit of British slang that has passed into Australian and New Zealand English, likely comes from obstreperous. Kidman has a fine sense for the feeling. Even in a collection of short stories on love, her women are stubborn, contrary, angry, and—worst of all—pushy. Gathered in their numbers, they stomp right over such designations. They defy the reflexively misogynist colonial vocabulary favored by those New Zealand journalists who once dubbed Kidman “Filthy Fiona” for her representation of female sexuality in her first novel, A Breed of Women, in 1979. The book became a bestseller, and Kidman kept writing. She’s now eighty-four and acclaimed for her services to New Zealand letters. Not least among her achievements is her work for the New Zealand Book Council (now called Read NZ Te Pou Muramura), where she established landmark accessibility programs that brought writers into classrooms, remote communities, and prisons. Along the way, she’s written more than thirty books. As critics like Sue McCauley have noted, Kidman has also made an impact on the country’s literary culture simply by being herself: a working mother, not university-educated, without “the right kind of family connections,” determinedly writing bestsellers. So her women are stroppy. What else would they be?

The “indestructible women” Kidman had the temerity to depict in A Breed of Women are everywhere in All the Way to Summer, a new anthology of thirteen short stories, written over some thirty years. (The earliest, “Mrs Dixon and Friend,” was first published in 1982.) The collection is organized around the theme of love and longing—not to be mistaken for love stories. As Doreen D’Cruz has observed, Kidman has long rebelled against the marriage plot as the fulfillment of the female bildungsroman. Her women-who-love are “bumptious,” “survivors,” “furious,” and “untamed.” They long for their lovers, their own unavailable husbands, their children. Particularly in those stories set in dismal small towns or isolated rural plots in mid-twentieth century Aotearoa (New Zealand), the women long for escape: for a bigger, more liberated elsewhere.

Kidman was born in 1940, in Hāwera, Aotearoa, and grew up in Kerikeri, in the far north of the country. Her mother’s family came over from Scotland on the fifth boat out of Europe and by the start of the twentieth century were prosperous settler colonial farmers. Her father, by contrast, was a rakish recent immigrant with a speaking style carefully cultivated to downplay his Irish roots: a “Johnny-come-lately,” Kidman wrote in her memoir At the End of Darwin Road (2008), chasing the colonial dream of “cheap fertile land for farming and cheap local labor that was easy to come by. Soon he would be landed gentry. He had the accent for it.” Like the young, class-aspirational Pākehā men in All the Way to Summer, he would be bitterly disappointed.

The term Pākehā is a Māori word used to indicate white settler colonial New Zealanders. Since the start of her career, Kidman has been interested in the role of class in Pākehā identity. Some Pākeha women in All the Way to Summer battle to put on Christmas roast dinners despite the heat of the Southern Hemisphere summer; others are so terrified of cooking lunch for their husband’s friends they simply don’t come home. Like Kidman’s own mother, one woman is mortified to find herself working as another Pākehā woman’s cook, in a wealthy British household recently transplanted from a military post in China. One keeps quiet about her Pākehā husband’s affairs with Māori women in support of his political ambitions, but when his time in government is over, and he suggests her daughter marry into a Māori family to repair a broken promise of kinship and land, she finds her English-accented voice: It will not do. Elsewhere, a townie girlfriend—already “a bit long on the shelf” at twenty-six—gets pregnant and is forbidden to return to her lover’s family farm. (Land and property preoccupy Kidman’s Pākehā characters, and are central plot points in more than half the stories here.) In a story set decades later, in the thick of Wellington’s counterculture, a woman’s self-consciously “prole” poet husband mocks her for being the daughter of a bank clerk—while she works as a teacher, pays the mortgage, and raises their children.

Kidman was active in the New Zealand women’s movement of the 1970s, and writes unblinkingly, now as then, of the importance of contraception and abortion as basic healthcare rights. Reminiscing on local mothers meeting for “coffee mornings” in the mid-1960s, she notes how “fear still lurked beneath the surface of ordinary domestic lives”: dressed in twinsets and pearls, the women admired the whiteness of each other’s cloth baby diapers hanging on the washing line, disapproved of work outside the home, and tallied what number of pregnancies would be manageable. Then a sea change arrived:

Somebody in our group had read about the pill being distributed to women of means, in America. There was talk that it would soon be available in New Zealand. The end of the messy undignified birth control methods we used, or of our dependence on our partners to use condoms or practise the rhythm method, or withdrawal, was in sight. Every drop of sperm counted, as couples discovered too often to their dismay. If this seems unduly intimate, for the majority of women, the reproductive period of our lives, how we had our children, or not, is one of the most central and enduring narratives, the stories we tell and retell, whether it be to others or our secret selves.

The above passage is from Kidman’s memoir So Far, For Now (2022), but it could serve as the introduction to the new anthology. The book’s characters divide into those who live before the radical social movements of the 1960s and 70s and those who live after; though the latter face their share of problems, their lives are transformed by reproductive freedom, a new sense of wherewithal, and a new vocabulary for their experiences. In one quietly astonishing passage from “Marvellous Eight,” Natalie, a television writer determined to lure her lover away from his wife, reads lines opposite another stand-in: Tess, a slightly older musician who, Natalie slowly realizes, is the much-talked-about “mistress” of the show’s foul-mouthed producer. The women have an immediate rapport, and soon stray from their lines:

TESS: (playing MRS OATES, the GRANDMOTHER) I’ve been watching my children for signs of improvement.

NATALIE: (playing the COUNSELLOR) And how old are the children?

TESS: Forty-nine and forty-three. (Puts the script down.) Natalie, that’s rich, I like it. My mother’s still waiting for me to improve. Are you saying she’ll never stop?

NATALIE: Probably not, mine’s in total despair, especially now I’ve left my husband. Should we stick to the script?

TESS: Yes, probably. It’s your turn.

As it unfurls, the exchange showcases not only the women’s exhilaration at having the language and space to openly discuss their experiences but also how crucial such conversations are in locating one’s desires, agency, and sense of self. With great gentleness, Tess shows Natalie the possibilities of “liberation” beyond impetuousness, toward something more like lifelong choice.

The interaction between fictional scripted dialogue and fictional conversation in “Marvellous Eight” is one of the most overtly playful narrative devices in All the Way to Summer. The short story form Kidman prefers, for the most part, is “the long, loping kind of story that is so different from, say, the well-made O. Henry story.” Coming across Alice Munro’s writing early in her experiments with the form in the early 1980s, she has said, “was like a validation.”

Like Munro, Kidman can take in a decade at a glance, observing the lives of women with a cool attention that is the more generous for its lack of sentiment. And, when it comes to anthologies on love, Munro’s Hateship, Friendship, Loveship, Courtship, Marriage is an obvious point of comparison. Love here is unpredictable, unreliable, shaggy. It’s constrained and impeded by the hierarchies and hypocrisies of colonial classism, sexism, and racism—and, for Kidman, the stifling, obstinate cultural insularity particular to Pākehā New Zealand.

Sometimes, however, love finds a workaround. A spiky, frustrated woman in Kidman’s “Silver-Tongued” falls in love with her husband after his death. In “Hats,” a story so adored by Kidman’s audience she had to give up reading it, as one might relinquish a crutch, two prospective mothers-in-law tussle over shared (though uneven) sacrifices that are a necessary part of becoming family. In “Stippled,” a couple who closely resemble Kidman and her late husband fall in love with their neighbor’s house and, after a scramble to buy it, live a life of great joy there. Their happiness represents a small personal triumph over classism and racism: “Jack” and “Jill” are an interracial couple, and their more affluent Pākehā neighbor had tried to block the sale. (Jill will not tell Jack that the neighbor inquires, from his nursing home, as to “how the Māori outfit was treating his house.” This poison has no place in their future: “They are who they are, and it’s their house now.”) In another moment of silence as a form of love, a middle-aged woman, looking back on her first teenage passion, elects not to tell an inquiring stranger the unhappy truth about the father she never knew.

Stories like “Tell Me the Truth About Love” and “All the Way to Summer” lope toward an intriguingly ambivalent tenderness that exemplifies the kind of love Kidman describes in “Red Bell”: “There are losses and separations and red beating hearts and flare-ups wherever our gaze rests. Sorrows become wounds, and we each carry the burden of one another.” Here, the narrator can only guide us so far, and love holds its secrets close.

Other stories tie up too neatly. The significance of the strange, distinctive opening passage of “A Needle in the Heart,” for instance, doesn’t unfold until almost the end of the narrative (a long one, at sixty-one pages). Unfortunately, shortly after the reader catches a glimpse of the shrouded, near-inarticulable tragedy inside “A Needle,” the author undermines her own subtlety by explaining the psychological crux of the story in bald terms.

Never mind. “A Needle in the Heart” is large enough to bear a critic’s quibble. Kidman’s protagonist, Esme, lives with something under her skin—a shard of the past that could kill her at any time. Her story bears some resemblance to that of Kidman’s mother-in-law: after an aborted education and short marriage to an English railway worker, Esme repeatedly uproots, withdrawing further and further from her early life. She’s disconnected from her Māori heritage and has little access to community. Middle age finds her a stranger at her son’s wedding, hovering unrecognized at the edge of the celebrations. (In getting Esme a seat in the last pew, Kidman softens the anguish of real life: her own mother-in-law stood watching the ceremony from outside the church, in the rain). From her first appearance on the page, Esme has an evasive, shadowy quality—she might be, in her own words, “a trick of the light.” It takes half a lifetime for Esme (and the reader) to understand that she isn’t driftless. She’s seeking herself, even though she has been told, time and again, that she is unworthy of love.

Evangeline Riddiford Graham is the author of poetry chapbooks La belle dame avec les mains vertes and Ginesthoi. Her recent writing can be found in Los Angeles Review of Books, Art News Aotearoa, Divagations, and Landfall. She hosts and produces the poetry podcast Multi-Verse.

This post may contain affiliate links.